- Home

- Lojze Kovacic

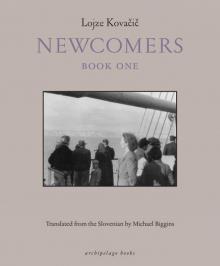

Newcomers

Newcomers Read online

Copyright © Slovenska matica, 1984,

published in arrangement with Michael Gaeb Literary Agency

English language translation © Michael Biggins, 2016

First Archipelago Books Edition, 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

First published as Prišleki I by Slovenska matica in 1984.

Archipelago Books

232 3rd Street #A111, Brooklyn, NY 11215

www.archipelagobooks.org

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Kovačič, Lojze.

[Prišleki. English]

Newcomers / Lojze Kovačič;

translated from the Slovene by Michael Biggins.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-914671-33-6 (paperback)

I. Biggins, Michael, translator. II. Title.

PG1919.21.O87P7513 2016

891.8′435—dc23

2015031469

The publication of Newcomers: Book One was made possible with support from Lannan Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-914671-34-3

v3.1

AND HE CONTINUED talking about himself without noticing that this couldn’t interest the others as much as it did him.

Leo Tolstoy, The Cossacks

SINCE THIS ISN’T A NOVEL, there isn’t a thing I can change about my hero.

From the epilogue to Book Three

A CERTAIN INDEPENDENCE exists by the grace of God. In each individual person. Every single one. Everyone carries his own head on his shoulders.

Alfred Döblin, A Trip to Poland

INTERESTING IS AN IMPORTANT WORD. Interesting doesn’t lead into that opaque, torturous “depth” that we know so well, and it doesn’t immediately lead to Goethe’s realm of the “mothers,” that popular German destination – interesting is by no means identical with entertaining. Translate it literally: inter - esse: amid being, which is to say amid its darkness and its glimmer. – “The Olympus of Seeming.” Nietzsche.

Gottfried Benn, A Double Life

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

That’s How We Left Basel

We Were

Vati Was Sitting by the Window

When I Opened my Eyes

When We Got Off the Train

Vati Came Back

The Door Moved Away

The Voices Had Almost Dwindled

When We Got to a Tree

Now It Became Easier to Walk

Now Both of them

When I Woke

Outside There Was

We Ate

This Latter Turned Out

Language

During the First Week

We Harvested Grain

She Wrote

Two Old Women

The House with Big Windows

Clairi Got Out at the Station

Finally the Time Came

Vati Sent us a Postcard

At Last

The Day before our Departure

All He Had

There Was Never a Light

Games of Every Possible Kind

I Should Have Known

On the Far Side

May Came …

Mrs. Gmeiner

Mr. Perme

Baloh and I

On Fridays

We Muddled Through

A Butcher Named Ham

I Was Left with

At the Start

Zdravko all but Disappeared

That Fall

One Day

Von Wem Hat Der Lümmel

Clairi Went Back

Vati Went Every Day

I Spent the First Few Days Leaning

Most Often

So That Was How I Managed

One of the Most Important Things

One Day

Several Times

Sergeant Mitič and Vati

The Germans

On Christmas

Town Square Filled up with Soldiers

THAT’S HOW WE LEFT BASEL. The Gerbergässli … rue Helder … Steinenvorstadt … Nadelberg … rue de Bourg. A lot of people came to our building, mostly police. Some wearing uniforms, others in plain clothes. Among the latter were some who looked like businessmen from the city center, while the wide-brimmed black satin hats on some of the others made them look like dancers from the variété. Two in uniform accompanied us with our most essential luggage across the Luisenplatz to the train station as people stopped and stared. We crossed a footbridge over a tributary where scarcely two hours before I had been playing with the yellow riverbed gravel at the foot of an artificial cliff. So we were going after all … So long, Basel!

WE WERE underway by one in the afternoon … I walked in and out of the compartment … the windows on both sides of the train car offered interesting views of the buildings and people … In the corridor I had a whole window to myself. Every now and then mother would call out to me not to lean on it so much or I’d get filthy, and to come back and join Vati and her in the compartment where they were sitting with Gisela … I ignored her, I felt ashamed to sit next to her … I pressed my ear up against the pane to drown out her voice. This was my first proper train trip … All I could remember of my first actual trip, when I was five years old and went with Vati to a sanatorium in Urach and back home to Basel, were the blue upholstered benches in the Pullman car … Now I could see what Basel was like when it got dizzy. At first like a fat, gray-green snake flying backwards, half on the ground, half in the sky … into a sort of huge sucking tube in the distance behind us … a proper dismemberment, a torrent, a hurricane. Then I saw a glass ball slowly swimming across the sky. I couldn’t tell whether it was the cupola of the exhibit hall at the fairgrounds or the main railway station. Buildings wriggled by under the train … I recognized some of them, but only from the street side. What was disappearing behind us was more interesting than what was coming toward us from up ahead. So I turned my head back … The red, star-shaped roof of the St. Alban’s gate that I’d run through at least a thousand times leapt into view … Adieu, adieu … then a long street appeared, perhaps the rue de la Couronne … with buildings washed yellow from exhaust or sulphur … A chain-link fence started to reach higher and higher up the window until it took over the whole field of vision, with numerous red tennis courts behind it. Vati and I had come here once on a long walk and watched from the shade as two couples played … The pictures in the window changed quickly, as though I had rapidly multiplying eyes. The tops of chestnut trees swarmed into view, and before I got a good look at the expanse of black, grassless earth full of bicycles and benches where they stood, I heard shouts and squeals and splashing water as the train went straight up over the white wall of the Eglisee. It was full of swimmers in bathing caps with inflatable balls in the water, and swimmers on the steps, on the wall … I didn’t see the big white ball with handles in the pool. I used it to learn how to kick in the water when Margrit and I came here … I noticed it by the wall, in the grass, where a bunch of hands were reaching for it … The white, square tower with its clock and pennants on halyards appeared … but the roof of the Eglisee had already evaded the train car in a wide arc, and all I could see at this point were some legs on the roof and a man’s feet … Then trees concealed the frolicking little hollow with their crowns.

It’s hot out there, I thought smugly, but in here there’s a breeze. All up and down the shady corridor the drapes kept battering against the windows and door

s … God had chosen a totally ordinary, totally stupid day like this to send me on this train trip … far, far away to a country where Vati had lived as a child and then later as a slightly older boy. Up ahead, beyond the buildings and trees that were flying back into Basel like drizzle … on the far side of the clouds and the arrogant mountain that kept retreating ahead of us, no matter how much the train tried to reach it … on the far side of some mountain slope I was going to encounter all kinds of things that were appropriate for my age … whether those were toys or buildings, animals or people, cars or airplanes. At night nothing like it would ever have occurred to me … and I had never even dreamed about Vati’s country, let alone imagined anything like it during the day …

After Vati’s and mother’s compartment, right next to the bellows-like connector, there was also a WC. It was so tiny and silly, like part of a gnome’s house. The toilet bowl shook and creaked crankily as I peed, as though it didn’t like being a toilet and would rather have been a milk jug, a chair, or at least a vase … The other door leading to the back of the train opened and people came out of it into the corridor … Through the narrow door I could see the other cars swaying like drunken houses … The people were carrying waxed yellow or round, red, lacquered suitcases that were too big and too heavy, they were as excited as I was, and happy … Their clothes exuded a smell that I inhaled with that of their skin and their hair. What a lucky coincidence that I was traveling with such childlike people, such scampish jokers … A splendiferous gentleman closed the car door behind him and put his bag in the compartment where Vati and mother were sitting. He stood by my window. He smelled of all different colognes, different down below than up above. He was wearing white trousers, a serious, striped jacket and a stiff red necktie. His eyebrows and mustache were equally thick and black, and could have been switched out with each other and replaced at random. He looked like a millionaire or a gangster from America … there was something of a boxer about him, or a trained horse, or even a camouflaged tank. Around his wrist, which he held next to the ashtray, was a watch that I’d seen in store windows: it had a green frigate riding atop its second hand. He smiled at me, which made me feel awkward, and I didn’t know where to look … and so he smiled again, revealing such brilliantly white, perfect little tiles between his red lips and black mustache that I couldn’t believe a person could have teeth like that … I lost so much time with smiles and furtive glances that in the meantime a completely different picture came through the window … We were riding through a pale blue sky with the sun up above in one corner of the window, like an unleashed crown. Dark red brick bell towers, one bigger than the next, appeared and rotated with pairs of saints, the peaks of their roofs articulated with spikes and balls and a different cross on top of each tower. The biggest one of them was probably the Münster with its fountain down below that I liked wading through up to my knees. Now we’re going, now we’re going, I sang into my lips … Suddenly there was a huge rumble and through the window steel girders flickered past this way and that, and below them the Rhine appeared with black bands of waves … On it were long, flat barges with closed hatches that carried coal and charcoal for irons … Above the Rhine stood a white building marked NEPTUN right on the water amid train tracks and coal cars, and through the window of the compartment I could also see the Mittlere Brücke with people and struts. The racket was so loud that I could have screamed and kicked doors and nobody would have scolded me for it … I touched the door and, as in some noisy dream, I wanted to say something special, but all I could say was “Wie schnell wir fahren,”* and then I shut up, disappointed … I started to hum Vati’s song, “Ljuba Kovačeva, two beers, we’ve got no cash …” of which all I understood was the surname, which sounded like ours. The infernal clamor died away and was replaced by a soundless silence, as though the train had become a balloon, a zeppelin, a glider slicing through the air with a whoosh as though it were silk … then came small, withered bushes and smaller houses … Basel was strangely disappearing through the windows … a building from the city had just been here, and now instead of it there was already a big hill. This was a speed I could appreciate … I could feel a jaunty tick-tock at the back of my head … I was traveling, traveling through an endless expanse to a country that had lots of horses waiting in stables, and I would unhitch one of them and ride him down to the river so he could drink water … and there would be red boats, so I could row from one riverbank to the other. On the rooftops there would be biplanes ready to take off, and I would fly around in them … over the rooftops and the water … and when they called me to dinner, I would land on the roof and climb down the chimney on a ladder back into the house. I pictured the short, stodgy airplanes that they used for acrobatics at the amusement park, with an open cabin for the pilot … one of them, a red one, would have my name stenciled on it … and I would fly all around in it, over the ponds and white gravel paths of the parks … If I stood by the window, the train went forward faster than if I left it alone … Outside all that was left was greenery, and only here and there some tree would try to finagle its way into the corridor, but of course it couldn’t. My legs became wooden from all the standing, and my eyes … and when the sun started to go down … a huge red tunic … I went back into the compartment.

*We’re going so fast.

VATI WAS SITTING BY THE WINDOW, with nothing to do of course, so he either looked out or dozed. Mother was still completely beside herself … red in the face and neck, she kept fidgeting … but thank God she was no longer complaining or whining. Our luggage, which had formerly been kept in the attic, was stowed on shelves up above: there were several brown and gray canvas bags with rusted corner pieces, a round carrying case made of shiny black leather, two cardboard suitcases and one made out of wicker. Gisela was sleeping with her head on a small comforter and her overcoat for a blanket. Mother offered me a slice of home-baked apricot bread on a napkin … I didn’t feel like it, I was more thirsty. “Iß, sonst wird’s dir schlecht.”* I ate one, two, three slices and then stretched out on the seat next to Vati. I didn’t want to rest my head on his knees, because I knew how he stank of fur down there, but also how uncomfortable my head would be. The gentleman from the corridor with the frigate on his watch sat and talked with both of them for a while. Was he Italian or French?

“Nach dreißig Jahren Leben in der Schweiz haben sie uns hinausgeworfen,”† Vati blurted out … and what other voice came next, but mother’s … here came the tears down her nose, and again I felt ashamed for her. Oh, I knew all of her reproaches by heart, even if I didn’t understand all of them … Vati turned attentively toward the dandified man.

“Das macht der Krinneg,”‡ the visitor answered thoughtfully. “Wenn es nicht die Gefahr von Krieg gäbe, wäre die Auslassung aus der Schweiz niemals passiert.”§

“Ach, wenn wir doch damals, in den zwanziger Jahren die schweizerische Staatsbürgerschaft angenommen hätten. Aber mein Mann wollte seine Länder zurück … Bis wohin fahren Sie mit uns?”‖

“Bis zu der Grenze,”a the gentleman said. He was the one who had locked the compartment door and had a key to the whole train car in his pocket.

They woke me up in the night with the electric light bathing the compartment in yellow. “Schnell, schnell, wach auf,” Vati said as I sank back into a pleated sort of sleep. He took hold of me and set me on my feet. I raised my arms over my head and fell to the floor. Gisela was already wrapped in a blanket and sleeping on mother’s shoulder. The gentleman was standing outside the train car. They hurriedly dressed me in my sailor’s coat with the anchor. Outside nothing was visible through the watery darkness except for some lights. I jumped from the high door out into the drizzly rain. We ran from the train that had brought us across tracks and ties that looked like ladders scattered over the gravel ballast. Mother ran with Gisela across a track toward a long, dimly lit roof. Vati was hurrying with me, pressing one of my hands to the handles of two suitcases he was carrying, because in the other he was carry

ing two more, while I had the round one in my other hand. Mother was shouting back at us, worried crazy as usual … In the light of the locomotive the rain turned into Christmas tree tinsel. The roof turned out to be a station with posters and numbers, but no people. Mother sat on a black iron bench holding Gisela in her arms, who was awake now and had the eyes of an ermine … Vati, accompanied by a gentleman disappeared into some black hole, because he had to take care of something with our green travel booklets. I was freezing. It was strange, that same day I’d been knocking around Basel. When I got to Barfüßerplatz across from Gerbergässli, Gritli had called to me from the other side. At first I thought she was trying to trick me, as she had often done to get me to go home. But this time she was shouting in such an urgent voice and with such an earnest face, even after a streetcar came between us, that I finally ran across the street on my own … She didn’t slap me, she didn’t touch me at all. Outside our building there was a policeman in a short cape. On the other side of the door there was chaos and running around, and suitcases were lined up one after the other on the steps, as though they’d walked out of the room on their own … “Schnell, schnell,” mother shouted from upstairs. “Wasche dich, wir fahren nach Jugoslawien.”b … Had I heard right? Was that even possible?… They literally ripped the clothes off of me, causing the buttons to fly, tossed me into the bathtub, soaped me up and scrubbed me so hard I had scratches, dried me with a towel, and dressed me in white … in a shirt with buttons that I tucked into my shorts. All the rooms – the workshop, the showroom, the salesroom – were full of strange gentlemen, plainclothes policemen, some of whom looked like businessmen and others like dancers, walking back and forth holding papers, writing things down, counting on their fingers and pushing us the whole time, “Schnell! Schnell!” We walked to the train station with our luggage, accompanied by two uniformed policemen and two in plain clothes. It was so hot that we all had dark spots on our clothes from sweating … At the station a nurse with a red cross on her cap met us. She wanted to take Gisela and me to the dispensary for coffee with milk, because we hadn’t had lunch. “Nein, das erlaube ich nicht,”c said mother. Lots of people crowded around … Mother held me by the hand and refused to let me go … but the nurse pleaded with her and gently took hold of me by the shoulder. Finally, with Gisela in her arms, mother went with me into a sooty office where the huge black plate of a locomotive loomed right outside the window. The nurse pushed a cup of gray-white coffee across the table … Mother picked it up with her left hand and tried it. “Ein schlechter, lauer Kaffee,”d she said. The nurse gave me a friendly nod. I knew that when adults were this nice it wasn’t right for children to turn down whatever they offered or else they could suddenly get angry. There was a gray membrane floating on top of the coffee. I took a swallow and a revolting, cold slime slid down my throat … I couldn’t get it down or out … I spat it back out into the coffee. I set the cup down and climbed out of the chair, regretting that I couldn’t oblige myself for the sake of the nurse. Vati arrived with the papers and black booklets that had little windows in them for our names. Finally we boarded the train, where I spent the whole time standing by a window. Mother of course was crying and complaining, which made me draw in my head and wish I could hide. The policemen and two gentlemen showed us the compartment we would be traveling in. They stood at the doors at both ends of the car, and there was a policeman in the corridor too … until the conductor came and locked the compartment. The train stood fairly far out from the main building and it wasn’t until it began to move that Clairi and Gritli appeared on the platform, both of them dressed like mother in white dresses and broad white hats. “Warum fahren sie nicht mit uns?”e I asked mother. “Clairi kommt später, das Gritli bleibt und wird alles machen bei den Behörden, daß wir zurückkommen.”f So we can come back? No, I don’t think so … Mother wept and kept casting looks at father as though he were some sort of lizard or crocodile. My sisters waved to us from next to a pillar. Clairi, Gisela’s mother, I liked better because she was always sad, but I looked at Margrit, who was mean, because she had begun to interest me more and more … As I was standing next to a pillar now, everything that had happened seemed as colorful and abrupt as in some comic strip … Despite the scrubbing, my fingernails were still black from the dirt and sand I’d been playing in by the water under the cliff … Vati came running alone out of the black hole and shouted, “Da ist der richtige Zug!”g as he pointed toward the headlights of a locomotive that was puffing in the rain, “woo-woo-woo” …

Newcomers

Newcomers